Evel Read online

Also by Leigh Montville

The Mysterious Montague

The Big Bam

Ted Williams

At the Altar of Speed

Manute: At the Center of Two Worlds

Copyright © 2011 by Leigh Montville

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Dick Cavett: Interview from The Dick Cavett Show, copyright © 1971, reprinted by permission of Dick Cavett.

FeelingRetro.com: Toy collectors’ comments, reprinted by permission of FeelingRetro.com.

The Montana Standard: “Citizens of Butte” letter, reprinted by permission of The Montana Standard, Butte, Montana.

Rolling Stone: Excerpt from “King of the Goons” by Joe Eszterhas from Rolling Stone, November 7, 1974, copyright © 1974 by Rolling Stone LLC. Reprinted by permission of Rolling Stone magazine.

Jacket design by Michael J. Windsor

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

eISBN: 978-0-385-53367-6

v3.1

For Colin Andrew Moleux

Born September 8, 2008

I had his action figure!! Mom picked it up for me at Amvets because she was too poor to buy me one new. My Evel came with broken parts … JUST LIKE THE REAL THING!

—Special Ed V, October 6, 2008,

WTOP message board

You can waste your time on the other rides

This is the nearest to being alive

—Richard Thompson, “Wall of Death”

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

1. Video

2. Words

3. Butte, MT (I)

4. Butte, MT (II)

5. Married

6. Insurance

7. Moses Lake, WA

8. Orange, CA

9. Gardena, CA

10. Caesars (I)

11. Caesars (II)

12. Movie

13. Action

14. Toys

15. Famous

16. Butte, MT (III)

17. Deals

18. America

19. Tests

20. Twin Falls, ID (I)

21. Whoosh

22. Twin Falls, ID (II)

23. Rebound

24. Wembley

25. Fort Lauderdale, FL

26. Chicago, IL

27. Hollywood, CA

28. Los Angeles, CA

29. Always, Forever Butte

Acknowledgments

A Note on Sources

Bibliography

Photograph Credits

About the Author

Photo Insert

Introduction

The first biography of Evel Knievel was written in the winter of 1970–71 in three days, maybe four, maybe five, hard to remember, in a house in Palm Springs, California, that was owned or borrowed or maybe just rented by George Hamilton, the actor. The sound of the typing—yes, an actual typewriter was used to do the job—was drowned out by the high-fidelity, 33⅓ vinyl majesty of a series of Strauss waltzes that were played constantly from the latest in stereophonic equipment, each note bouncing off the white walls and white ceilings and white furniture and out the open windows to the swimming pool, where assorted women sunbathed without the stifling confinement of clothes.

The first biography of Evel Knievel, of course, was a screenplay.

The writer was twenty-seven-year-old John Milius. He had been hired on the cheap, a flat fee of $5,000, and asked to pound out a script about a thirty-one-year-old motorcycle daredevil from Butte, Montana, who had begun—but only begun—to capture the attention of assorted pockets of the American public. The deal was enhanced by the delivery of some fine Cuban cigars, secured from Colonel Tom Parker, best known as the manager of singer Elvis Presley, and the promise that upon completion of his duties Milius would be treated to an afternoon of what he called “commercial affection” with one of the undressed women at the pool.

He tore into his work. A macho, firearm-loving graduate of the University of Southern California School of Film, frustrated by the fact that his asthma had kept him out of the Vietnam War, which he saw as the great historic moment of his time, Milius was part of a group of young writers, directors, and producers like Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas who were in the first throes of success in the film industry. They were all grabbing ideas out of the air, slamming them down on paper, hurrying, hurrying, trying to get things done in a rush because they didn’t know how long their good fortune would last.

Milius was in the midst of that hurry-hurry stretch of creativity. He had written part of the script for the movie Dirty Harry, starring Clint Eastwood, which soon would be released …

(“I know what you’re thinking—‘Did he fire six shots or only five?’ ” Clint/Harry said in the most memorable monologue. “Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I’ve kind of lost track myself. But, being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you’ve got to ask yourself one question, ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well do ya, punk?”)

… Work on Jeremiah Johnson, which would star Robert Redford, was pretty much finished, and Milius’s next project was The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, which would star Paul Newman. The pieces of dialogue for Apocalypse Now (“I love the smell of napalm in the morning”) already were floating around in his busy head. Evel Knievel fit in there quite well too.

The idea of a guy, some crazy son of a bitch, jumping over an ever-growing string of parked cars on a motorcycle was revolutionary, different, funky, extreme. The story offered a combination of noise, smoke, crashes, broken bones, white motorcycle leathers, American individualism, and a long middle finger lifted directly at all forms of authority. This was a definite plus in a time of long middle fingers everywhere pointed at all forms of authority. Add a dash of romance, maybe a warning about trying any of these stunts at home. Shake well. Pour.

This was fun.

“The whole thing was modern and absurd,” Milius said years later. “This character going over trucks on his motorcycle, riding through flaming hoops and all that. I just settled down and did it. I played that one record of Strauss waltzes over and over again. (I love Strauss waltzes.) I wandered around the white furniture, white walls, felt I soiled anything I touched. There was a bumper pool table in the house. I took breaks. I learned how to play bumper pool.”

This was a lot of fun.

Facts were not a problem. Milius had never met Evel Knievel and had never been to the copper-mining splendor/grime of Butte, Montana, but that didn’t matter much. First of all, the foundation of Knievel’s life story was filled with half-truths, semi-truths, and flat-out whoppers anyway, a collection of tall tales designed by the man himself to make people perk up and pay attention. He would say anything to make himself more marketable. Second, the task was not so much to write an actual portrayal of Evel Knievel’s life, but to write a vehicle for George Hamilton to look very good on a motorcycle in the leading role. Hamilton had put the production together, hoping to energize a career that had grown fuzzy in the wilds of network television with a couple of canceled series. He wanted to add a little hair and grit to his perceived image as a well-tanned playboy.

A disclaimer (“based on incidents in Evel Knievel’s life”), tagged on the end of the story, allowed Milius to do just about anything. He invented characters, invented dialogue, invented scenes that never had happened in Knievel’s life. He had a car disappear, swallowed into the hollowed-out, heavily tunneled ground of Butte, directly at an adolescent Knievel’s feet (never happened). He had an aging rodeo cowboy die, thrown from a bull, right before Knievel’s first jump (never happened). He took single sentences from Knievel’s résumé and inflated them into fat, pop-art events, quite different from what actually happened.

The Milius version of the character had tongue planted well into cheek, wry and funny most of the time. A chase with the Butte police, Knievel on motorcycle, police in a too-slow patrol car, was played completely for laughs. The same was true for Knievel’s courtship with his wife as he rode his cycle straight into a sorority house, past the stammering housemother, up the stairs to the second floor, through squealing, pajama-clad residents, and back down the stairs and out the front door with his bride-to-be holding on to him for dear imperiled life. A dwarf with a cowboy hat was written into the script as a friend of Knievel’s. Knievel was written as a hypochondriac, a comic contrast to all of his experience with doctors and hospitals. The language often was outrageous. The paying customers all wanted to see Knievel “splatter,” a comic-strip word that Milius used over and over again.

The story was told in a series of flashbacks as the hypochondriac, madcap risk-taker prepared for his longest jump of all, nineteen cars, all American cars, “not a Volkswagen or Datsun in the row,” at the Ontario Motor Speedway. The ending, after Knievel successfully cleared the nineteen American cars, not a Volkswagen or Datsun in the row, showed him continuing to ride, flying through the air to the edge of the Grand Canyon, his biggest proposed jump of all, the ultimate challenge that he always promoted. Milius gave him these self-inflated words to say in closing:

Important people in this country … celebrities like myself, Elvis, Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, we have a responsibility. There are millions of people that look at our lives and it gives theirs some meaning. People come out from their jobs, most of which are meaningless to them, and they watch me jump twenty cars, maybe get splattered. It means something to them. They jump right alongside of me … they take the bars in their hands and for one split second they’re all daredevils. I am the last gladiator in the new Rome. I go into the arena and compete against destruction and I win. And next week I go out there and do it again. At this time, civilization, being what it is and all, we have very little choice about our life. The only thing really left to us is a choice about our death. And mine will be glorious.

Fade to credits.

Milius shoveled his work to Hamilton, who was staying at the Plaza Hotel in New York, in long daily telegrams. Hamilton pinned the telegrams to the hotel walls, delighted with each arrival. This was his exact vision of the movie. Milius was delighted that Hamilton was delighted. They thought they had put together a suitable motorcycle extension of Easy Rider, the movie that had been a recent cultural and box office hit and made stars out of Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson.

Hamilton, as soon as he returned to Los Angeles, wanted to show the finished script to Knievel. He found him at the low-rent Hollywood Land Motel on Ventura Boulevard, holed up in a room with a Kotex pad wrapped around an injured leg and a bottle of Wild Turkey in close proximity. Hamilton later described the meeting in his autobiography I Don’t Mind if I Do. The meeting did not start well. He said that Knievel told him to read the script out loud.

“I declined,” Hamilton said in the book. “[I said,] ‘I don’t read scripts. I act them.’

“Read,” Evel demanded and literally put a gun to my head. And cocked it. Read, he said. And so I read. For more than two hours. I gave the performance of a lifetime, as if it might be my last, which was clearly the case. Evel liked what he heard. He liked it so much that he began adopting John’s fictionalized dialogue and style as his own, life imitating art this time. Thank my lucky stars. Problem was that Evel got so into it that he became as grandiose as a Roman emperor.

Fade to credits.

The movie was not a great hit. It was shot in Butte and Los Angeles, released in the summer of 1971. Critics didn’t swallow Hamilton’s change from pretty guy to tough guy. The public was diverted to films like The French Connection, Billy Jack, Fiddler on the Roof, Summer of ’42, and The Last Picture Show. Evel Knievel mostly came and went, made a few bucks for everyone concerned, and was consigned to that long video afterlife that now exists for movies everywhere.

The big winner in the operation was the subject. He received only a reported $25,000 for his rights, but the value of the publicity that came from the movie was incalculable. He was splattered—nice word—across America. His name was spread everywhere in ads, on theater marquees, in casual conversation. The made-up story, added to his own story, pushed his exploits further into the main stage spotlight that he always had craved.

Milius, the screenwriter, finally met Knievel on the set in Los Angeles. He liked him well enough, but really didn’t get to know him. Knievel showed him the scars from his assorted crashes, which Milius thought looked like so many zippers on a human body, strange to behold. Knievel tried to explain the sequence of surgeries, doctors going back through the same openings to readjust bent pins and bones after each calamity, but Milius got lost somewhere in the explanations.

More memorable was a story he heard about Knievel rather than from Knievel. This came from that promised afternoon of “commercial affection” that was the reward for finishing the script on time.

The woman in question was lovely, professional, and probably quite skilled, but Milius never really could be a judge of that. He was young, impetuous, and very fast in his affection. Left with a lot of time on the clock, the couple sat around and talked, covering a bunch of subjects. One of the subjects was Evel Knievel. The woman in question said she previously had been a gift to Knievel for a similar afternoon of commercial affection. She said it had been remarkable mostly for the client’s instructions.

“You don’t have to do anything special for me just because of who I am,” the woman said Evel Knievel said. “I want to be treated like a normal, mortal man.”

Milius was astounded by the words.

The real-life character was even more grandiose, more outrageous, more preposterous, had a larger ego, than the cartoon-style character in the movie. Wow. You don’t have to do anything special for me because of who I am. That would be something a caliph, a count, okay, a Roman emperor or some other libidinous head of state might say. It’s okay. I want to be treated like a normal, mortal man. Maybe the pope would say this to a member of the faithful, maybe a general to a private on KP. A man who rides motorcycles for a living?

Wow.

Who was this guy?

Almost forty years have passed since this first cockeyed tale of Evel Knievel played on the screen of the local movie theater, which no doubt has long since closed and now is a full-service pharmacy or purveyor of designer coffee drinks. The man himself died on November 30, 2007, succumbed to pulmonary fibrosis, a quite different death, at age sixty-nine, than anyone envisioned, and he now lies in a plot at the Mountain View Cemetery in Butte close to the fence, across busy Harrison Avenue from the Wal-Mart where his ex-wife Linda worked not so long ago.

Who was this guy?

Cue the Strauss waltzes. Tell those assorted women—they’d probably be in their sixties now—to put down their grandchildren and get back out by the pool. Clothing is optional.

Maybe we can figure it all out.

The typing begins. Again.

&

nbsp; 1 Video

He walks onto the black-and-white screen a few minutes after midnight wearing a zebra-striped leisure suit. There is a quick thought that something might be wrong with the television this late at night. Static of some kind in the neighborhood. An electrical malfunction. No, the stripes only move when Evel Knievel moves. This is his outfit.

He is a one-man test pattern. The collar on the leisure suit is exaggerated, Edwardian, huge. The pants flare out at the end, bell-bottoms. His white leather kick-ass boots, which stick out from the edges of the bell-bottoms, would be suitable for either a well-dressed gang fight or an open-ended night in a Las Vegas cocktail lounge. The stripes on the leisure suit—back to the stripes—are random, run every which way, as if somebody had splashed white paint across a black background. The effect is dramatic. He is a work of modern art, certainly a piece of work, a cat on the prowl.

He is here to be on The Dick Cavett Show. He has dressed for the occasion.

“My next guest is an incredible character,” Cavett tells the studio audience at the Elysee Theater on West Fifty-eighth Street in New York City.

He’s a motorcycle daredevil driver. All his life he’s been doing death-defying feats. Death has nearly defied him several times. His longest jump was fifty yards, a fifty-yard jump over the fountains of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. This jump did not go well. You may have read about it. Or seen some still photos of it. He has some film with him of what happened. He seems to spend his life, or what he has left of it, it sometimes seems to me, seeing what he can do to shorten it. Incredible things he does … Will you welcome the legendary Evel Knievel.

The Bob Rosengarden Orchestra plays “Daisy Bell” in the background, better known as “Bicycle Built for Two,” a family standard written in 1892. The audience applauds. The “incredible character,” the “motorcycle daredevil driver,” walks across the stage with a slight limp in his left leisure-suited leg.

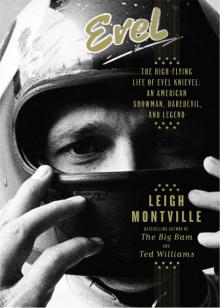

Evel

Evel